The man behind the most popular female comic book hero of all time, Wonder Woman, had a secret past: Creator William Moulton Marston had a wife — and a mistress. He fathered children with both of them, and they all secretly lived together in Rye, N.Y. And the best part? Marston was also the creator of the lie detector.

Harvard professor and New Yorker contributor Jill Lepore reveals this and other surprising details about Marston in the new book The Secret History of Wonder Woman.

"I got fascinated by this story because I'm a political historian and it seemed to me there was a really important political story that had been missed that's basically as invisible as Wonder Woman's jet," Lepore tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross.

There are a lot of people who get very upset at what Marston was doing ... 'Is this a feminist project that's supposed to help girls decide to go to college and have careers, or is this just like soft porn?'

Marston, who was a famous psychologist, made up Wonder Woman in 1941. He was interested in the women's suffrage movement and in Margaret Sanger, the birth control and women's rights activist — who was also his mistress's aunt.

A feminist icon, Wonder Woman was an Amazon who forced people to tell the truth with her magic lasso. She was a controversial figure in the 1940s because of her overt sexuality and her link to bondage. Her costume was inspired by Marston's interest in erotic pin-up art.

"There's no simple story here," Lepore says. "There are a lot of people who get very upset at what Marston was doing. ... 'Is this a feminist project that's supposed to help girls decide to go to college and have careers, or is this just like soft porn?' "

Interview Highlights

On Wonder Woman, the character

Wonder Woman is an Amazon from an island of women who left ancient Greece to escape the enslavement of men. And they lived on Paradise Island and had eternal life. And a plane crashes on their island carrying a man — and Wonder Woman's mother decides he needs to be brought back to where he came from because they can have no men on Paradise Island.

So she stitches for Wonder Woman this star-spangled costume, and Wonder Woman flies in her invisible jet with her man-captive Steve Trevor, who is a U.S. military intelligence officer, back to the United States. This is in 1941.

And [she] comes to call herself "Wonder Woman" because she has superhuman powers that only Amazons have. She has bracelets that can stop bullets. She has a magic lasso — a golden lasso — [and] anyone she ropes has to tell the truth. And she's got the cool jet.

On the secret life of Marston and his mistress

It's so bizarre. I think they thought it was very funny. In a certain way it is very funny — like that they're putting one over on everybody. The funniest thing of it all to me is [they have] this really triangular family arrangement, but in the '30s [Marston's mistress] Olive Byrne takes a job as a staff writer at Family Circle magazine writing advice for housewives. Family Circle, which starts in 1932, [is] a giveaway at the grocery store [and] the stories that she writes are sort of a "how to raise your children" in the most conventional possible way.

On how the early suffrage movement influenced Marston

Marston has all kinds of ties to the early progressive-era suffrage and feminist and birth control movements — sort of an uncanny number and complexity of ties. ...

[They] begin when he, as a Harvard freshman in 1911, is caught up in a big controversy on campus. In the fall of 1911, the Harvard Men's League for Women's Suffrage invites the incredible Emmeline Pankhurst to campus to speak in Sanders Theatre, which is like the largest lecture hall on campus. The Harvard Corporation is terrified — women are not allowed to speak on campus ... so [eventually ] Pankhurst is banned from speaking on campus. And this [is] kind of a big fracas across the country.

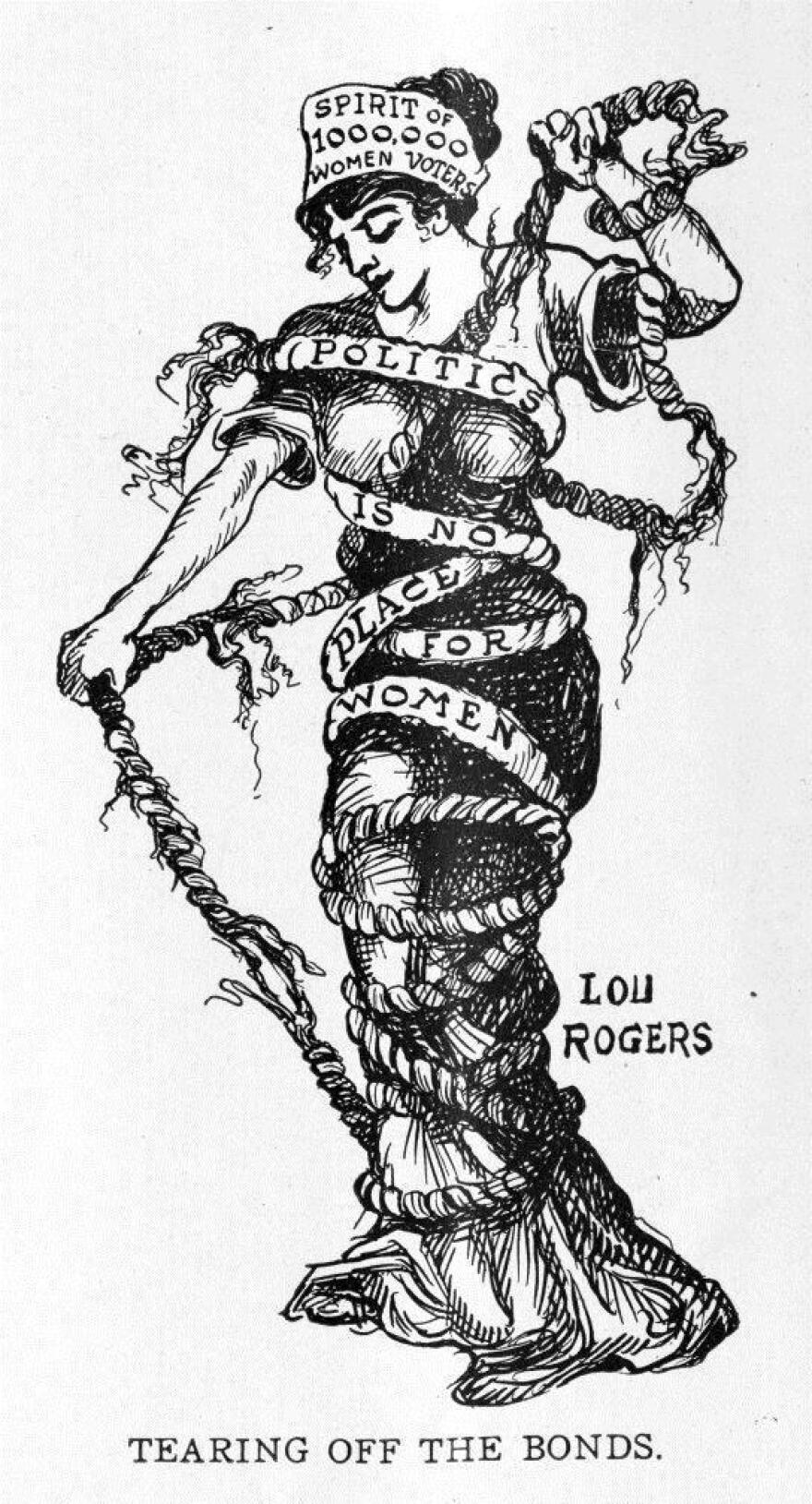

Even to that alone, there's so much in there that reappears in Wonder Woman, 30 years later, when Marston creates Wonder Woman in 1941. ... One of the things that's a defining element of Wonder Woman is that if a man binds her in chains, she loses all of her Amazonian strength. So in almost every episode of the early comics, the ones that Marston wrote [Marston stopped writing Wonder Woman in 1947], she's chained up or she's roped up ... and she has to break free of these chains. ... That's [what] Marston would always say — "in order to signify her emancipation from men." But those chains are a really important part of the feminist and suffrage struggles of the 1910s that Marston had a front-row seat for.

On the imagery of chains

[During the suffrage movement], women chained themselves to the gate outside the White House in protest. There were suffrage parades, women would march in chains — they imported that iconography from the abolitionist campaigns of the 19th century that women had been involved in. ...

Chains become a really important symbol. Women in the wake of emancipation in the aftermath of the Civil War really turn to the imagery of chains and enslavement and the language of enslavement to talk about the ways in which they have not yet been fully emancipated.

On Marston entering the comic-book world

Comic books start in 1933, '34, and then the first superhero, Superman, starts in 1938. Batman follows in 1939, but then immediately there's a pretty big crisis around comic books, which become scandalous [because of their violence] and people start wanting to burn them. People think they're bad for kids and that Superman is a fascist and Batman carries a gun for a while. ... There's a pretty big wave of critics damning comic books.

The guy who publishes Superman, M.C. Gaines, decides he wants to hire someone to help him out, and he reads Olive Byrne [Marston's lover's story] in Family Circle about how William Moulton Marston thinks comic books might be good for kids. So he calls Marston into his office.

On a need for a female superhero

If you think about the problem with the comic books [then], Marston says they're [full of] "blood-curdling masculinity." That's the problem — that they're just too violent, it's the violence, but it's also the domination. The reason why Superman looks like a fascist to some literary critics is he's kind of a demagogue, but he also overpowers everybody.

In the shadow of what's going on in Europe [the Nazi uprising], it's very terrifying to imagine kids worshiping this Ubermensch. And so [Marston] says [to Gaines], "Look, if you had a female superhero, her powers could all be about love and truth and beauty, and you could also sell your comic books better to girls. And that would be really important and great because she could show girls that they could do anything."

On the Varga Girls, inspiration for Wonder Woman's costume

The Varga Girl centerfolds appeared in Esquire in the 1940s. ... The Varga Girls are really different from earlier conventions of female beauty. ... There's a kind of leggy, sultry, athletic, healthy, high-heeled perky something. There's a kind of cosmopolitanism to the Varga Girls. ... They're not all-American, they have a kind of exoticism that Wonder Woman has, too. She's not supposed to be from the United States, and that's kind of a piece of it. They're wearing the skimpiest possible swimsuit-like costumes — their shirts are always unbuttoned and they're enticing.

On how Wonder Woman is a complex character

[Wonder Woman is] a tangle and it's a puzzle kind of like [how] Lady Gaga is. You look at Lady Gaga and you're like, "Huh, what do I think about her?" You know? ... Wonder Woman looks like that for me, too. She didn't look like that when I started, but now I'm like, "She's way more complicated and rich —there's no wonder why she has permeated the culture and has lasted so long. There's a lot going on there."

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.